The Catch-22 of Sodium-Ion Battery Adoption

Sodium-ion battery chemistry isn’t just about the sodium-ion chemistry.

The successful adoption of emerging battery chemistry is less about incremental performance gains or scientific breakthroughs than the complex economic and systemic factors that determine whether a technology is viable for broad implementation.

To understand why sodium-ion chemistry faces headwinds in real-world adoption despite the many stated benefits on paper, we need to both zoom in to understand cell behaviors and zoom out to see the big picture.

The compatibility challenge

For emerging battery chemistries like sodium-ion, the ability to procure input materials and produce cells at an acceptable yield or cost is a poor indicator of real-world success.

Sodium-ion chemistries look good in theory:

For a chemist or material scientist, sodium-ion chemistry meets various performance requirements.

From the “oblivious” user’s perspective, sodium-ion batteries have a low cost of ownership.

For a CFO or business modeler, sodium-ion chemistry is abundant, low-cost, and can be sourced from virtually anywhere.

Ecologically, sodium-ion batteries are non-toxic and easy to recycle.

However, sodium-ion battery chemistry is an engineering nightmare.

Adopting this new chemistry requires a wholesale redesign of the supporting equipment (i.e., anything connected to the batteries), which is made for established chemistries (e.g., lithium cobalt and LFP) and fundamentally incompatible with the behaviors of sodium-ion cells.

It’s all about the discharge curve

Equipment connected to batteries (e.g., inverters, motor devices, etc.) must accept the pack’s output voltage range. It’s much easier and cheaper to design and build equipment for batteries with a narrow output voltage range. The products are more cost-effective, smaller, and lighter.

A broader discharge range requires more complex technology. The equipment, in turn, is more expensive while the efficiency drops. So, what determines that range? It’s the battery chemistry.

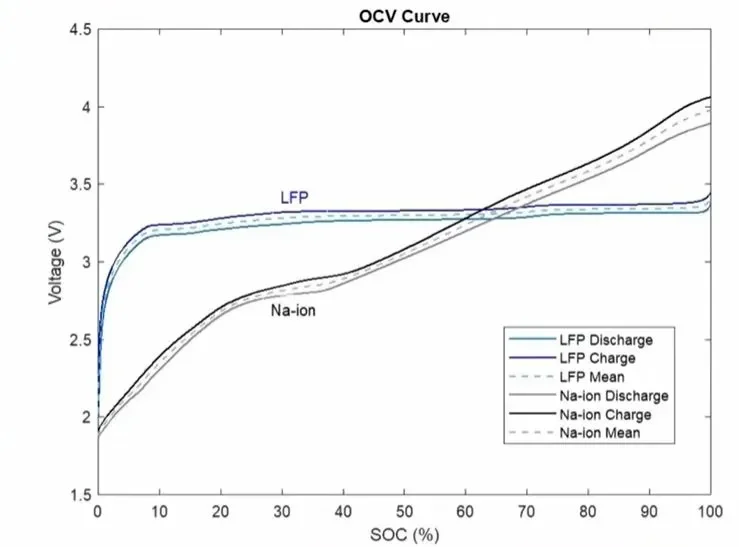

Lithium iron phosphate (LFP) cells have a rather flat discharge curve. The useful range of a cell falls between 3 and 3.5V, with most of the discharging occurring at 3.2 to 3.3V. Since the difference between the lowest and highest voltage from a battery pack is small, equipment using this chemistry is the most cost-effective and efficient.

Meanwhile, lithium cobalt chemistry has a voltage range of 3 to 4.2V per cell. Product builders must design equipment to accept this wider spread. The resulting solutions are less efficient but still economically feasible, mostly because the chemistry’s high energy density offsets the drop in efficiency.

However, sodium-ion chemistry is a different story. These cells have a discharge range of 1 to 4.5V. Currently, there’s no supply or market for equipment that can serve such a wide range cost-effectively.

While building a solution is possible, the size, weight, cost, and reliability penalties of supporting such a wide voltage range will cancel the economic benefits of sodium-ion chemistry — even if we achieved the economies of scale (and we’re a long way away).

To make sodium-ion batteries somewhat compatible with existing technologies, some engineers artificially limit the discharge range. However, this workaround leaves substantial storage capacity on the table. The drop in efficiency quickly gets to the point where LFP becomes a better option.

The turning point of sodium-ion battery adoption (or any new battery chemistry)

In the foreseeable future, the success of sodium-ion battery adoption won’t be determined by raw material availability, manufacturing capability, or recycling technology. The bottleneck will be the ability to use the stored energy cost-efficiently.

If we stick with conventional wisdom and battery technology, the entire ecosystem must change before widespread adoption and economies of scale become a reality.

For example, diesel is 30% more efficient than gasoline. Yet, it existed for over half a century before the scale tipped and a global distribution system came into existence to support widespread, cost-efficient application.

A viable cradle-to-grave business model determines the success of a new technology in a situation where everything relies on everything else. (What isn’t on today’s interdependent global supply chain and economy?)

However, turning a business model of such magnitude into reality requires substantial investment from the public and private sectors. Without the resources, we can’t test all the dependencies and ecosystem constraints at a meaningful scale.

Yet, we can’t count on organizations betting on chemistries that look good on paper but are unproven at scale in decade-long implementations.

How do we solve this catch-22?

What if… we could decouple the electrification ecosystem from battery characteristics?

Instead of requiring a practical cradle-to-grave business model before adopting a new battery chemistry, what if we could decouple battery characteristics and behaviors from equipment requirements?

In other words, what if we could program battery packs of any chemistry to generate an output voltage within a very narrow and precise range, compatible with any existing equipment, and allowing for future adoption of cost-efficient solutions?

An equipment-agnostic battery pack.

Software-defined batteries (SDBs) built on the Tanktwo Operating System (TBOS) allow product builders and operators to sidestep battery chemistry adoption hurdles. The Dycromax™️ architecture automatically routes and re-routes strings within a battery pack to ensure a consistent output voltage, which can also be adjusted on the fly via a software interface.

With our advanced battery software, a battery pack of any chemistry can work with any existing equipment. When you’re ready to upgrade to a new technology, you have the flexibility to implement the most cost-effective and reliable solutions simply because a battery system’s output voltage ceases to be a constraining factor.

SDBs mean: No trillion-dollar bets. No need to turn everything attached to and dependent on battery solutions upside down. Faster, cheaper, and frictionless adoption of new chemistries.

SDB and TBOS turn the value proposition on its head by making batteries adapt to existing equipment supply and availability — enabling new chemistries like sodium-ion to reach critical mass at an organic rate without a huge leap of faith.